Neural Networks: The Potential

Part 3 of 3

This is the third, and final, installment in a three Part series on the role of Artificial Intelligence in Online Dispute Resolution. Insight into the neural networking aspects of AI is drawn from an interview with Jacob Menashe, Doctoral Candidate in Computer Sciences at the University of Texas at Austin.

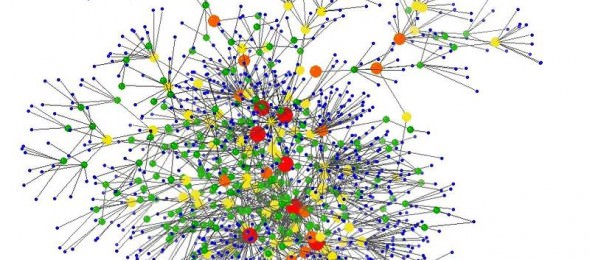

There is great potential for adapting neural networks for ODR purposes. A neural network works like this:

1. Neural networks are formed from different nodes, or “neurons,” connecting to other nodes.

2. Neurons receive inputs from other neurons and, subsequently, they produce an output that is either intended to be sent along to connected neurons or they create their own output directly.[1]

3. Each output signal is dependent on a processing element, which is also dependent on the input to the processing element.

4. Each input is gated by a weighting factor that determines the amount of influence that the input will have on the output.[2]

5. This weighting factor’s strength is adjusted autonomously by the processing element as data is processed.[3] Put another way, the topology of the way the neurons are connected is where the machine learning takes place.[4]

Neural networks learn over time through repetition.[5] Essentially, neurons become correlated by one firing and causing the other to fire, an occurrence that gets stronger the more it is repeated, which is replicated with algorithms in neural networks.[6]

For example:

If there are three neurons—A, B and C—where A and B connect to C, a particular algorithm can determine that A is a very strong predictor of whatever desired result is identified (outcome Z), whereas B is not a strong predictor of Z.[7] Thus, A will have a stronger weight than B and this connection will become refined through repeated iterations.[8] These iterations generate data and train the neural network to become better and more sophisticated in handling the inputs.[9]

A particularly amazing aspect of neural networks is that the programmer “does not have to understand fully the problem the network is trying to solve.”[10] Many machine learning systems require the programmer to have prior knowledge about the domain and insert that knowledge into the system.[11] Neural networks, on the other hand, “are good at discovering solutions that are not expected.”[12]

Although neural networks technology is not yet foolproof and the field still must make sizeable advances, eventually the neural networks will be able to figure out a problem so long as a goal is described.[13] The technology is only about twenty to thirty years from empowering computers to take care of specialized tasks, like arbitration, so long as there is adequate “training” (iterations) before the program is launched.[14]

Computers may ultimately be proved to be better than humans at cerebral tasks because they can account for more data and have fewer biases.[15]

One major problem with the use of neural networks is the lack of explanation the system provides. People want to understand how and why a decision is made. When one uses neural networks to solve a problem, the output provides only the solution, not the reasoning.[16]

The decision process employed in neural networks is abstract.[17] The programs find associations, but they do not necessarily “reason” in the way the term is applied to human decision-making.[18] Although this is in line with some forms of arbitration (where no reasoned award is given), it is incongruous with many parties’ expectations and desires.

One example is the use of neural networks in deciding whether or not a bank should provide a loan to an individual: the computer may be better than agents at picking which customers would default. This use is not widespread because people do not trust the outcome of the computer and, in the event of rejection, want to understand why they were denied. People need and deserve to understand the rationale behind these important decisions.[19]

Even with this problem, the potential use of neural network technology in ODR could lead to a number of interesting applications. Although it is feasible that neural network programs could function as the arbitrators themselves, this application is rather unlikely for a number of reasons:

- Disputants may desire a reasoned award or may perceive the need for a check on the output of the program.

- The perception (whether or not warranted) that computers cannot achieve just results will lead parties to choose human arbitrators.

- Complex disputes may require human interaction and human management.

Although neural networks will not replace arbitrators, they can be helpful tools for arbitrators and aid in quick, efficient, and cost-effective resolution of disputes.

One potential aid could be analogous to the way IBM Watson, the computer program that beat human contestants on Jeopardy!, is currently being used to aid doctors.[20] The program is used “to create an outcome and evidence-based decision support system. The goal is to give oncologists located anywhere the ability to obtain detailed diagnostic and treatment options based on updated research that will help them decide how best to care for an individual patient.”[21]

In arbitration, the database could help arbitrators have instant access to a variety of evidence-based best practices and data relevant to the case—essentially an AI law clerk. This information (at this speed and cost) could provide invaluable benefits to the arbitration process.

Another possible application of neural networks is in e-discovery. Potentially, both disputants could plugin to, download, or otherwise network with a computer program that could aid in the speed, accuracy, and fairness of discovery.

A neural network program could be designed to comb through the thousands of gigabytes of data and seek specified documents relating to specified parameters and rules chosen by the arbitrator, the disputants, or the party who drafted the arbitration clause. Though it may be difficult at first to get parties to agree to have a “mole” search their servers, businesses might adopt its use with developed trust in the program, increased cost-savings, and a possible independent review before the “discovery record” is published.

As one of the major complaints about arbitration recently has been a prolonged discovery that is becoming more similar to litigation,[22] the potential impact of AI discovery for ODR and arbitration in general is great. Both cost and time can be saved by a neural network program’s (nearly) instantaneous discovery.

The disputants’ understanding of the application of neural networks to the dispute is key in using it effectively. Once parties come to understand, trust, and appreciate the cost-savings provided by neural-network-assisted arbitration, this form of machine learning is bound to be instrumental in changing the face of dispute resolution.

Conclusion: Where AI and ODR Should Go

There is a bright future for the use of AI in ODR. Programs that can aid an arbitrator in fairly and quickly resolving a dispute will not only effect cost-savings, but also be a great asset to businesses and arbitrators alike. The question becomes which direction the field of AI ODR should go to maximize benefits to the alternative dispute resolution field.

One problem with AI may take care of itself. Although humans tend to be distrustful of computers, which may result in underuse of AI programs, exposure to artificial intelligence in the dispute resolution field, as well as in everyday life, will increase trust.

Psychologists call this impact the mere-exposure effect:

The more someone uses something, the more that person prefers the use of that thing. Every time someone uses a smartphone, that person is signaling trust in the device, as well as creating a preferential relationship. Over time, and with the increase in computer technology and AI available (Siri for example), people will become more comfortable with the role of computers in their lives—including in their dispute resolution processes.

Before that comfort level is reached, the use of AI must be advertised, demonstrated, and implemented.

Arbitrators can help this process by using a number of available ODR devices:

- Electronic document submission

- Chat room negotiations and mediations

- Skype depositions, hearings, or testimony

- Any other number of ICT programs that will facilitate a quicker and cheaper dispute resolution process

As the stakeholders in arbitration, the disputants, become more comfortable with these technologies, they will become more comfortable with the role of AI as an aid to both them and the arbitrator.

Perhaps the most important factor for AI in ODR is advertising its benefits to the client. Arbitration holds a unique position as a private contractual arrangement and as such can be the frontrunner in dispute resolution. Civil courts, necessarily, move much slower in adopting and using new technologies. Arbitration can be a true alternative, a testing ground, for parties to find ways to resolve their disputes at minimal administrative cost. If the benefits are there, the use will be as well.

Certainly human judgment plays a role: IBM Watson should not be resolving complex questions about the Constitution. However, as an aid to the implementation of arbitration, AI can be the next great tool. For arbitration to maintain its benefit and remain businesses’ top choice for dispute resolution, arbitrators need to incorporate new technologies to ensure that it remains what has brought it this far: cheap, quick, private, and fair.

Grant is a J.D. and Master of Public Affairs candidate at the University of Texas. He will graduate in 2014. In addition to law, Grant enjoys hiking, soccer, and watching Law & Order.

![Digital Disagreements: Artificial [Intelligence] Arbitration](https://i0.wp.com/www.disputingblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/Calatrava-Bac-de-Roda-Bridge-.jpg?resize=150%2C150&ssl=1)