The United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit has issued a decision stating a federal judge committed error when he ruled on a party’s motion to dismiss a case before he considered whether the dispute should be arbitrated. In Silfee v. Automatic Data Processing, Inc., et al., No. 16-3725 (3d Cir., June 13, 2017), a man, Joshua Silfee, filed a lawsuit against his former employer, ERG Staffing Service (“ERG”), in the Middle District of Pennsylvania. In his complaint, Silfee claimed the company’s payroll policies violated state law because workers were required to utilize a debit card that imposed a variety of fees.

In response to Silfee’s lawsuit, ERG filed a motion to compel the dispute to arbitration based on an arbitration agreement between Silfee and ERG’s payroll vendor, Automatic Data Processing. In addition, ERG also filed a motion to dismiss Silfee’s case based on the merits of his state law claims against the company. The district court opted to delay consideration of ERG’s motion to compel arbitration and denied the company’s motion to dismiss the case.

On appeal, the Third Circuit stated:

The Federal Arbitration Act manifests a “liberal federal policy favoring arbitration agreements” and was passed with the purpose of moving litigants “out of court and into arbitration as quickly and easily as possible.” Moses H. Cone Mem’l Hosp. v. Mercury Constr. Corp., 460 U.S. 1, 22–24 (1983). Section 4 of the FAA provides that “[a] party aggrieved by the alleged failure, neglect, or refusal of another to arbitrate under a written agreement for arbitration may petition any United States district court for an order directing that such arbitration proceed in the manner provided for in such agreement.” 9 U.S.C. § 4. Because “arbitration is a matter of contract [and is] predicated upon the parties’ consent,” a court ruling on a motion to compel under § 4 must first determine if the parties intended to arbitrate the dispute. Guidotti v. Legal Helpers Debt Resolution, L.L.C., 716 F.3d 764, 771 (3d Cir. 2013) (citations and alterations omitted).

The District Court erred in bypassing this § 4 inquiry to rule on ERG’s motion to dismiss. Arbitrability is a “gateway” issue, so “a court should address the arbitrability of the plaintiff’s claim at the outset of the litigation.” Reyna v. Int’l Bank of Commerce, 839 F.3d 373, 378 (5th Cir. 2016) (emphasis added). In deciding a motion to compel arbitration, the role of the court “is strictly limited to determining arbitrability and enforcing agreements to arbitrate, leaving the merits of the claim and any defenses to the arbitrator.” Republic of Nicaragua v. Standard Fruit Co., 937 F.2d 469, 478 (9th Cir. 1991). Thus, after a motion to compel arbitration has been filed, the court must “refrain from further action” until it determines arbitrability. Sharif v. Wellness Int’l Network, Ltd., 376 F.3d 720, 726 (7th Cir. 2004) (citation omitted). District courts may not alter this sequencing: “By its terms, the [FAA] leaves no place for the exercise of discretion by a district court, but instead mandates that district courts shall direct the parties to proceed to arbitration on issues as to which an arbitration agreement has been signed.” Dean Witter Reynolds, Inc. v. Byrd, 470 U.S. 213, 218 (1985).

According to the appellate court, the lower court also erred when it applied the Third Circuit’s holding in Guidotti to the case at hand:

The District Court committed two errors in this regard. First, it did not recognize that the standards laid out in Guidotti are truly dichotomous. Because either the Rule 12(b)(6) or the Rule 56 standard will apply, there are no circumstances in which Guidotti does not provide a “clearly-articulated standard of review.” App. 9. Second, the District Court misstated the applicability of the Rule 12(b)(6) standard, reasoning that it “is to be applied only in cases where a party does not question the arbitrability or applicability of the arbitration agreement.” Id. But that interpretation would render the Rule 12(b)(6) standard a nullity; if a party has filed a motion to compel arbitration, then the other party necessarily questioned arbitrability. See 9 U.S.C. § 4 (explaining that a motion to compel is filed after “the failure, neglect, or refusal of another to arbitrate”). Rather, if a party moves to compel arbitration based on an authentic arbitration agreement that is attached to the complaint, the Rule 12(b)(6) standard is appropriate unless “the plaintiff has responded to a motion to compel arbitration with additional facts sufficient to place the agreement to arbitrate in issue.” Guidotti, 716 F.3d at 776.

The Court of Appeals next examined the facts of the case at hand before stating:

Though both Silfee and ERG urge us to rule on arbitrability, we think it imprudent to do so. “It is the general rule, of course, that a federal appellate court does not consider an issue not passed upon below.” Singleton v. Wulff, 428 U.S. 106, 120 (1976). Here, the District Court did not identify—much less analyze—any of the parties’ competing arguments regarding arbitrability. Accordingly, we will remand to the District Court for consideration of ERG’s motion to compel arbitration in the first instance.

Finally, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit vacated the district court’s order and remanded the case.

This case was labeled not precedential by the appellate court.

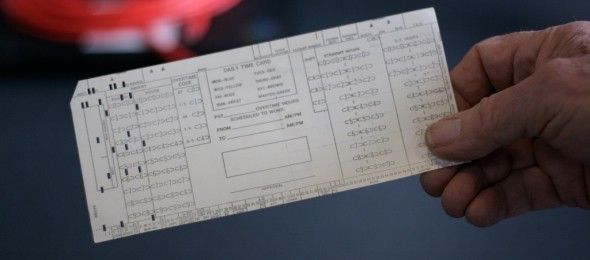

Photo credit: Marcin Wichary via Foter.com / CC BY